Volcanic Eruption

The first documented eruption of Mayon Volcano was in 1616, and has erupted a total of 52 times since, with the last eruption on 2018. The predominant type of eruptive activity is characterized by one or a combination of lava fountaining, generation of pyroclastic and lava flows and formation of tall eruption columns. Most eruptions evolve from discrete explosions to near continuous lava fountaining; other eruptions involve short periods of inactivity within one eruptive episode. Some precursors associated with Mayon Volcano eruptions are: increased background seismicity levels, change in color and increase in volume of steam emission, presence of crater glow, rumbling sounds and fissuring at or near the summit.

Contrary to popular belief, Mayon does not erupt every 10 years and there is no evidence supporting this concept. The nature of Mayon Volcano’s eruptions are different in types and magnitude and can be described as minor explosive, major explosive or major non-explosive. Minor explosive eruptions are characterized by minor ash explosions. The duration of each eruption period usually lasts from one day to several days.

Major eruptions are three different types: Plinian, Vulcanian and Strombolian. Each styles have its own characteristics and degree of violence. If the magma about to erupt is volatile-rich, then an explosive eruption is to be expected. Degassed or volatile-poor magmas favor non-explosive eruptions. Plinian and Vulcanian types are explosive while strombolian eruptions are non-explosive. A single eruption may exhibit only one eruption style or may have two or three types throughout the duration of the event. More often, Mayo’s eruptions are Vulcanian in nature. Except for the Plinian eruption in 1814, all other historical eruptions have been Vulcanian or Strombolian or a combination of both. There are two common sequences exhibited by Mayon during its eruptive stage: One starting with explosive ejection of ash and pyroclastic flows followed by lava flows (1968 eruption) and the other with initial non-explosive extrusion of lava culminating in violent ejections of pyroclastic flows (1984 eruptions). Solely strombolian activities usually starts with minor ash ejections and end with “quiet” lava effusion as in the 1978 eruption.

Strombolian Eruption

The most distinctive feature of this eruption styles is the quiet extrusion of lava from Mayon’s summit crater or from point in the summit. This type produces discrete but minor explosions of ash and incandescent coarse pyro clasts, particularly volcanic bombs. Such explosions produce a spectacular display of fire fountaining. During the 1978 eruption, hot molten lava continuously but slowly poured out from the crater and cascaded downward to flow along the gully towards Camalig. This lava flow then formed an elongated (4.2 Km) and incandescent stream of molten volcanic rock material 20m thick and 250m wide at its front. The first phase of the 1984 activity was a fairly strong Strombolian type, characterized by a small pyroclastic flow events followed by strong lava effusion. The 1984 lava flow lies alongside the 1968 and 1978 lava flows.

Vulcanian Eruption

This is the most common type of Mayon Volcano eruption. It often produce a moderately violent but intermittent unsustained explosions involving ash, lapilli, blocks and bombs, producing pyroclastic flows and fine tephra fall materials; an eruption column with a distinctive “cauliflower” shape may be visible from a distance. Vulcanian eruptions may characterize a single eruption, or it may either precede or follow a Strombolian event. During the 1968 eruption, the first phase was Vulcanian in nature. Pyroclastic flows swiftly cascaded down towards the lower slopes near the municipalities of Camalig and Guinobatan. In 1984, the second phase of the eruptive period was also Vulcanian. Voluminous pyroclastic flows were deposited towards Legaspi and Sto. Domingo.

Plinian Eruption

This eruption is the most violent of all three types. It is characterized by extreme violent and continuous sustained ejection of pyroclasts, mostly volcanic ash and lapilli particles, with attendant formation of a tall umbrella-like eruption column. The eruption of Mayon in 1814 could be classified as a major Plinian type.

Precursory Signs:

In general, the following are the precursory signs that usually precede Mayon Volcano’s activities:

- Increase in seismicity level

- Inflation and tilting of the volcano slopes near the crater

- Change in color of steam emission from white to brown or light gray due to presence of ashes

- Change in the volume of steam emission due to increase in temperature

- Presence of crater glow with increasing intensity due to presence of magma

- Rumbling and other subterranean noises

- Fissuring rockfalls and landslides at or near the crater due to pressure exerted by rising magma

- Unusual animal behavior

Hazards Associated with Mayon Volcano Eruption

Volcanic hazards vary greatly in type, areal extent, duration and destructive potential. The associated hazards are a consequence of Mayon’s three different eruption types discussed previously. In general, “small” and non-explosive eruptions produce few hazards while “big’ eruptions have many associated hazardous phenomena. These phenomena pose serious threats to life and poverty in varying degrees in areas around the volcano. The associated hazards due to eruptive products and areas vulnerable to such hazards.

Hazards from Mayon can be classified into two broad types:

- Flowage Hazards (ground-huggers)

- Lava flows

- Pyroclastic flows (pyroclastic density currents)

- Lahars

- Non-flowage Hazards

- Ballistic fragments

- Large-tephra fall

- Ashfall

Lava Flow

Lava flows are relatively large, coherent and elongated streams of incandescent molten materials that usually ooze non-explosively from the volcano’s summit crater or from a point near the summit that cascade along ravines and gullies. Lava flows are extremely hot (about 1000 degrees centigrade) when they leave the vent. They cascade down along the upper cone but move very slowly upon reaching the basal slopes. Their moderately high viscosity makes them move slowly (a few meters per hour), this characteristic viscosity also tends to retard the spreading out of the flows far from their source. The farthest distance reached by a Mayon lava flow is just six km from the volcano crater.

Pyroclastic Flow

The term “pyroclastic” – (now called pyroclastic density current) is derived from the Greek words pyro (fire) and klastos (broken) – describes materials formed by the fragmentation of a “new” magma and solidified “old” volcanic rock by explosive volcanic eruptions.

Pyroclastic flows, sometimes called ash flows or nuees ardentes (French for “glowing clouds”) are superhot, often incandescent and turbulent blasts of volcanic fragments (boulders, pebbles, sand and dust) and hot gasses that sweep along close to the ground at hurricane speeds, sometimes as great as 500 kph. Being ground-huggers, they are horizontally directed and devastate large areas along topographic depression and gullies through which they encroach. They are fatal to nearly all life and property in the affected area.

Pyroclastic flows issues from Mayon Volcano summit crater and are commonly produced during explosive Vulcanian type eruptions either by backfall (collapse) of pyroclastic materials from a tall eruption column or by boiling-over directly from its vent. These ground-huggers pyroclastic and gas mixtures tend to follow existing gullies or crevices the main flow. This ash cloud can be easily drifted by the prevailing surface windstream. The flowing hot debris stops when enough gas has been lost from the suspension, leaving a thick but loose deposits consisting of a mixture of boulders and ashes.

Pyroclastic flows are extremely hot (up to 1000 degrees Centigrade) upon leaving the vent but are “cooler” when they reach downslope areas. They still remain hot, even incandescent or molten when deposited.

Tephra and Ballistic Fragments

Tephra consists of explosively ejected slots of either new incandescent magma or fragments of older solid rock. These particles are explosively hurled into the air from the crater by the force of an erupting volcano. It is synonymous with the word pyroclastic. Tephra particles are of various sizes – ash (less than two mm in size), lapilli (two to 64 mm in size), bombs (greater than 64 mm in sizes). Lapilli and bombs are kinds of large tephra.

Ashfall

Volcanic ash is a tiny or powdery tephra. It is produced when rising magma in upper conduit is fragmented or pulverized due to expansion of compressed gasses. The pulverized materials are then blasted upward from the crater during explosive eruptions.

Because of its small size, ash can be hurled high upward (as high as 25 km from the crater), and can remain airborne in the atmosphere for prolonged periods. It can also be carried by prevailing winds farther than any volcanic material. It is the most common hazard from Mayon. Vertical ash ejections often accompany pyroclastic flows.

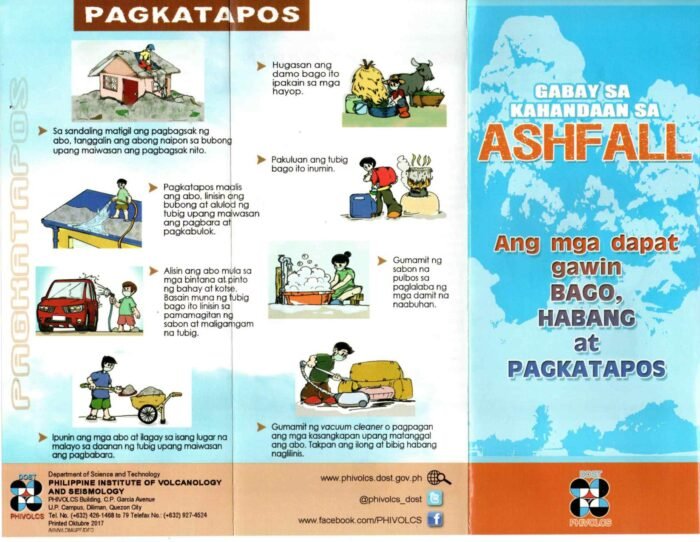

*IEC on Ashfall by Phivolcs

Lahar

Lahars (an Indonesian term), sometimes called mudflows or volcanic debris flows, are flowing mixtures of volcanic debris and water. Geologists classify lahars into two types: primary or hot lahars which are associated directly with volcanic eruptions and secondary or cold lahars which are caused by heavy rainfall. Both types occur in the area surrounding Mayon Volcano.

Lahars from Mayon originate from its summit crater but from the upper and middle slopes of the volcano. Lava and pyroclastic materials perched on the steep slopes are eroded and then mobilized by heavy rains, thus causing a debris-water mixture (like the consistency of wet concrete) to cascade and flow downslope of the volcano. Lahars usually follow pre-existing gullies and ravines. Upon reaching the lower slopes, they spread out and leave thick and widespread deposits.

Depending on the slope on which they flow, lahars span a wide range of velocities and dimensions. In Cotopaxi Volcano (Ecuador 1877), lahars traveled 300 kms at an average speed of 27 kph. The 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens triggered lahars that traveled for 35 kms as fast as 120 kph. In 1985, melting of snow and ice by an eruption of Nevado del Ruiz in Columbia triggered a gigantic lahar that flowed along a major river to engulf the town of Armero (50 kms from the crater) and bury 20,000 residents in just less than an hour.

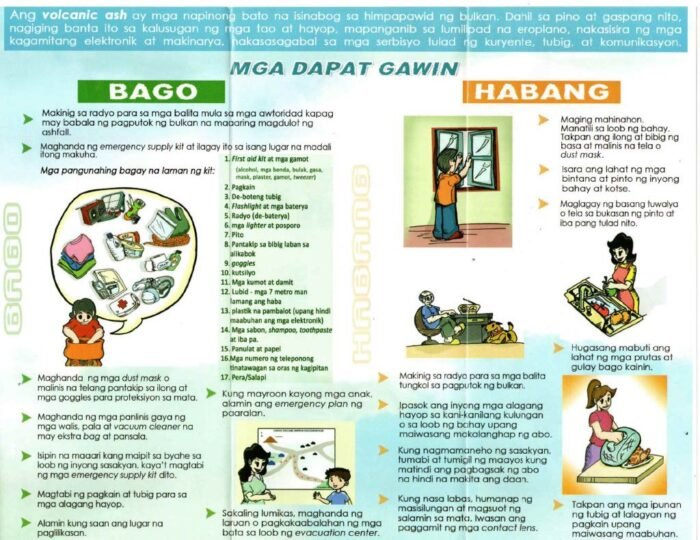

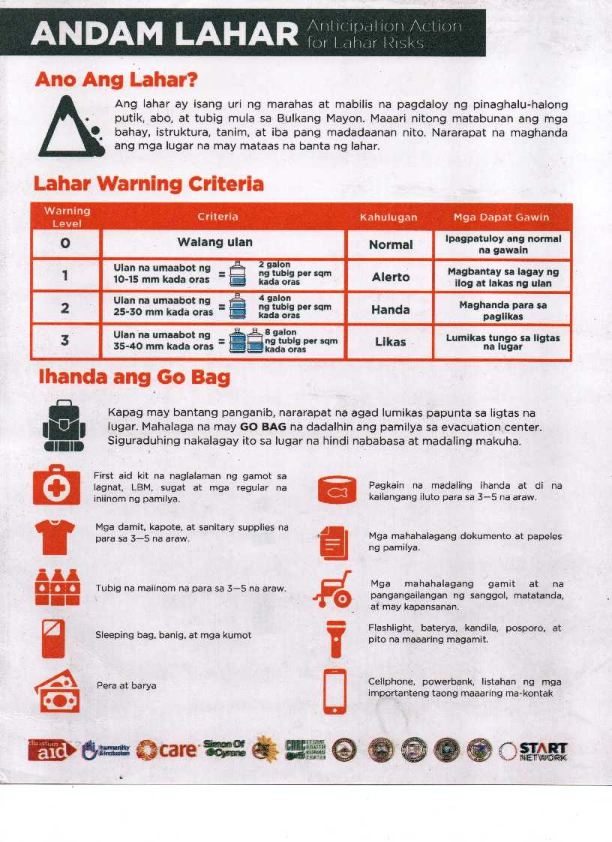

*IEC on Lahar by APSEMO

Source: Mayon Operation, PHIVOLCS

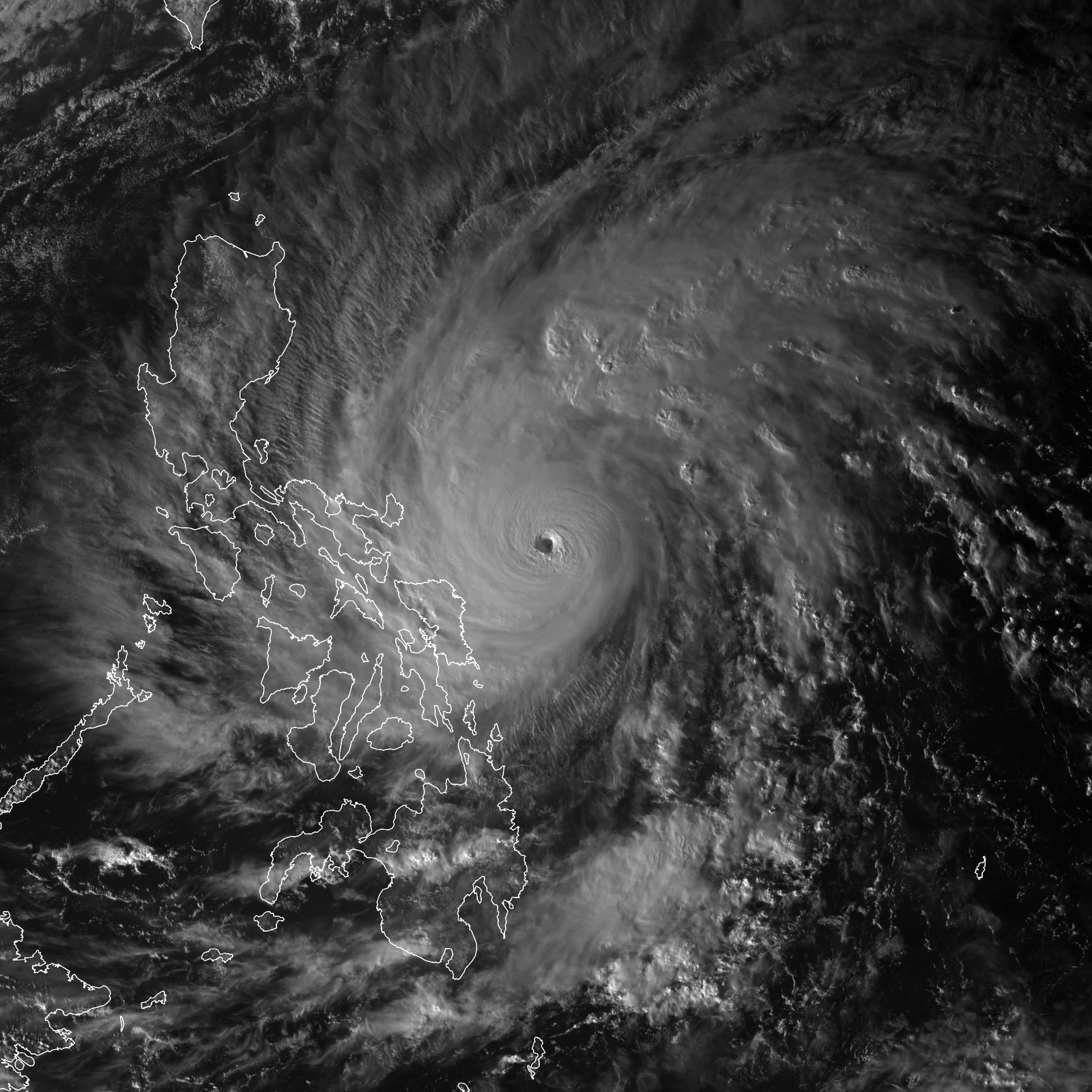

Tropical Cyclone

Albay, has historically been highly vulnerable to tropical cyclones due to its location along the typhoon belt and proximity to the Pacific Ocean. Major events include Super Typhoon Reming (Durian) in 2006, which caused devastating lahars from Mayon Volcano, flooding, and widespread destruction; Super Typhoon Rolly (Goni) in 2020, which brought extreme winds, storm surge, and heavy rainfall, prompting large-scale evacuations; Severe Tropical Storm Kristine in 2024, notable for record rainfall and flooding; and Tropical Storm Fengshen in 2025, which triggered evacuations due to rainfall and storm surge forecasts. Historical cyclones such as Typhoon Irving (1982) and Typhoon Betty (1980) also caused significant property damage and displacement. According to PAGASA, the hazards associated with these cyclones in Albay include strong winds, heavy rainfall leading to flash and riverine floods, storm surge in coastal areas, rough seas, lahars and landslides, particularly in areas surrounding Mayon Volcano, making preparedness and timely evacuation essential for local communities.

WHAT IS A TROPICAL CYCLONE?

Oceans and seas have great influence on the weather of continental masses. A large portion of the solar energy reaching the sea-surface is expended in the process of evaporation. These water evaporated from the sea/ocean is carried up into the atmosphere and condenses, forming clouds from which all forms of precipitation result. Sometimes, intense cyclonic circulations occur which is what we call the Tropical Cyclones.

Tropical cyclones are warm-core low pressure systems associated with a spiral inflow of mass at the bottom level and spiral outflow at the top level. They always form over oceans where sea surface temperature, also air temperatures are greater than 26°C. The air accumulates large amounts of sensible and latent heat as it spirals towards the center. It receives this heat from the sea and the exchange can occur rapidly, because of the large amount of spray thrown into the air by the wind. The energy of the tropical cyclone is thus derived from the massive liberation of the latent heat of condensation.

CLASSIFICATION OF TROPICAL CYCLONES

Tropical cyclones derive their energy from the latent heat of condensation which made them exist only over the oceans and die out rapidly on land. One of its distinguishing features is having a central sea-level pressure of 900 mb or lower and surface winds often exceeding 100 knots. They reach their greatest intensity while located over warm tropical waters and they begin to weaken as they move inland. The intensity of tropical cyclones vary, thus, we can classify them based upon their degree of intensity.

The classification of tropical cyclones according to the strength of the associated winds as adopted by PAGASA as of 23 March 2022 are as follows:

TROPICAL DEPRESSION (TD) – a tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of up to 62 kilometers per hour (kph) or less than 34 nautical miles per hour (knots).

TROPICAL STORM (TS) – a tropical cyclone with maximum wind speed of 62 to 88 kph or 34 – 47 knots.

SEVERE TROPICAL STORM (STS), a tropical cyclone with maximum wind speed of 87 to 117 kph or 48 – 63 knots.

TYPHOON (TY) – a tropical cyclone with maximum wind speed of 118 to 184 kph or 64 – 99 knots.

SUPER TYPHOON (STY) – a tropical cyclone with maximum wind speed exceeding 185 kph or more than 100 knots.

EFFECTS OF A TROPICAL CYCLONE

Tropical cyclone constitutes one of the most destructive natural disasters that affects many countries around the globe and exacts tremendous annual losses in lives and property. Its impact is greatest over the coastal areas, which bear the brunt of the strong surface winds, squalls, induced tornadoes, and flooding from heavy rains, rather than strong winds, that cause the greatest loss in lives and destruction to property in coastal areas.

STRONG WINDS

A squall is defined as an event in which the surface wind increases in magnitude above the mean by factors of 1.2 to 1.6 or higher and is maintained over a time interval of several minutes to one half hour. The spatial scales would be roughly 2 to 10 km. The increase in wind may occur suddenly or gradually. These development near landfall lead to unexpectedly large damage.

TORNADOES

Tornadoes are spawned by tropical cyclones and are expected to occur in about half of the storms with tropical storm intensity. These are heavily concentrated in the right front quadrant of the storm (relative to the track) in regions where the air has had a relatively short trajectory over land. These form in conjunction with strong convection.

RAINFALL AND FLOODING

Rainfallassociated with tropical cyclones is both beneficial and harmful. Although the rains contribute to the water needs of the areas traversed by the cyclones, the rains are harmful when the amount is so large as to cause flooding.

STORM SURGE

The storm surge is an abnormal rise of water due to a tropical cyclone and it is an oceanic event responding to meteorological driving forces. Potentially disastrous surges occur along coasts with low-lying terrain that allows inland inundation, or across inland water bodies such as bays, estuaries, lakes and rivers. For riverine situations, the surge is sea water moving up the river. A fresh water flooding moving down a river due to rain generally occurs days after a storm event and is not considered a storm surge. For a typical storm, the surge affects about 160 km of coastline for a period of several hours.

LAHARS AND LANDSLIDES

Lahars and landslides are significant hazards in Albay, particularly around Mount Mayon, during tropical cyclones. Lahars also called mudflows or volcanic debris flows are mixtures of volcanic debris and water. Geologists classify them into primary (hot) lahars, triggered by volcanic eruptions, and secondary (cold) lahars, caused by heavy rainfall. Tropical cyclones bring intense and prolonged rains that saturate volcanic ash, soil, and loose rocks on Mayon’s slopes, forming fast-moving slurries that can flow rapidly down river channels and valleys, destroying homes, infrastructure, and farmland. Similarly, landslides occur when saturated soils on steep slopes lose cohesion and slide downhill, blocking roads, damaging property, and endangering lives. Both hazards are intensified during cyclones, making early warning and evacuation critical for communities in high-risk areas.

SOURCE: PAGASA

Earthquake

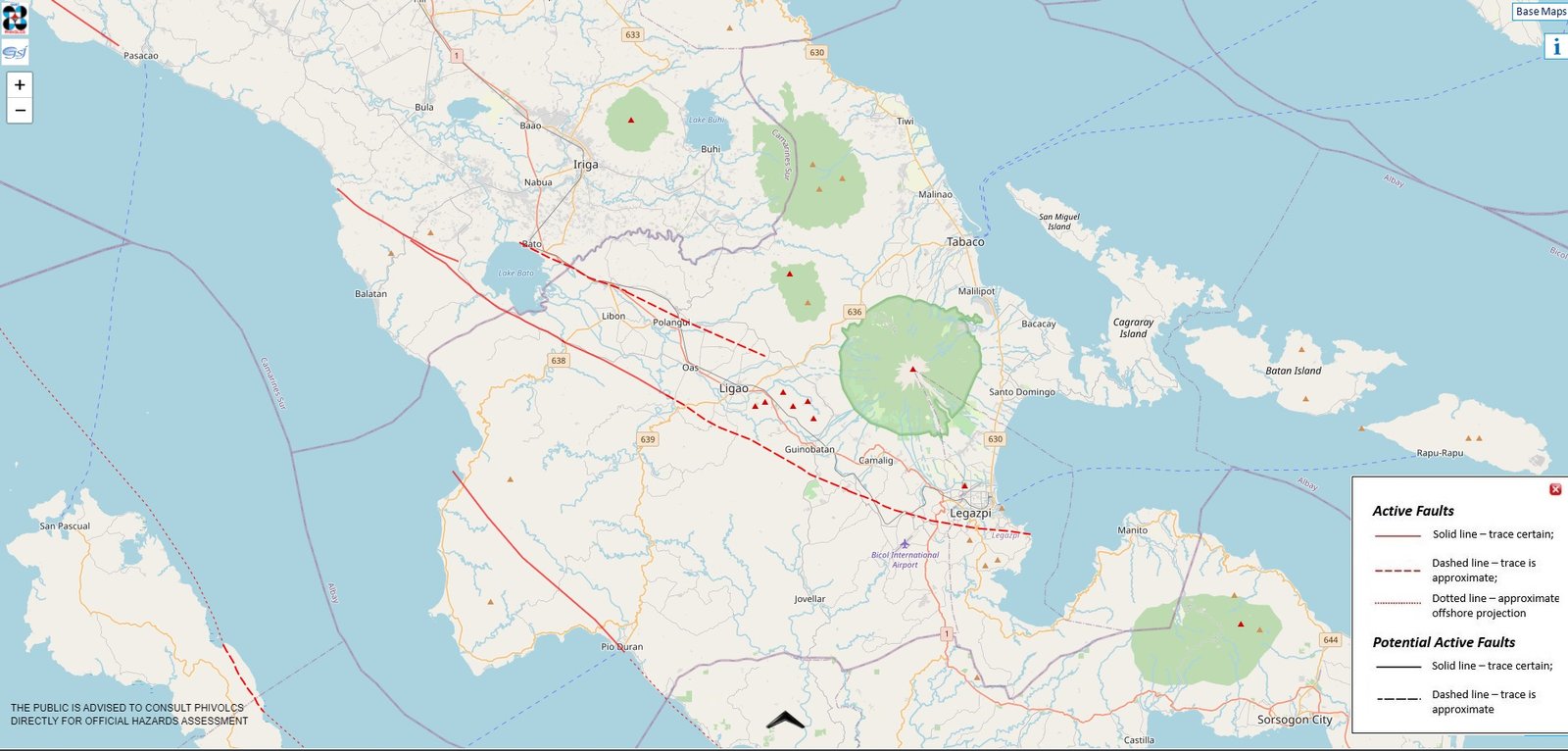

Earthquakes in Albay Province are primarily influenced by the region’s active tectonic setting and volcanic activity, particularly Mayon Volcano, as monitored by the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS). The province experiences both tectonic earthquakes, caused by movement along faults and nearby subduction zones, and volcanic earthquakes, which are associated with magma movement and rock fracturing beneath Mayon Volcano. PHIVOLCS regularly records clusters of volcanic earthquakes during periods of increased volcanic unrest, indicating internal volcanic processes rather than major fault movement. While most earthquakes in Albay are generally mild to moderate, strong ground shaking can still pose hazards such as structural damage and landslides, especially in steep and volcanic areas. PHIVOLCS continuously monitors seismic activity in the province and issues earthquake information and safety advisories to help reduce risks to communities.

WHAT IS AN EARTHQUAKE?

An earthquake is a weak to violent shaking of the ground produced by the sudden movement of rock materials below the earth’s surface.

The earthquakes originate in tectonic plate boundary. The focus is point inside the earth where the earthquake started, sometimes called the hypocenter, and the point on the surface of the earth directly above the focus is called the epicenter.

There are two ways by which we can measure the strength of an earthquake: magnitude and intensity. Magnitude is proportional to the energy released by an earthquake at the focus. It is calculated from earthquakes recorded by an instrument called seismograph. It is represented by Arabic Numbers (e.g. 4.8, 9.0). Intensity on the other hand, is the strength of an earthquake as perceived and felt by people in a certain locality. It is a numerical rating based on the relative effects to people, objects, environment, and structures in the surrounding. The intensity is generally higher near the epicenter. It is represented by Roman Numerals (e.g. II, IV, IX). In the Philippines, the intensity of an earthquake is determined using the PHIVOLCS Earthquake Intensity Scale (PEIS).

TYPES OF EARTHQUAKE

There are two types of earthquakes: tectonic and volcanic earthquakes. Tectonic earthquakes are produced by sudden movement along faults and plate boundaries. Earthquakes induced by rising lava or magma beneath active volcanoes is called volcanic earthquakes.

EARTHQUAKE MONITORING SYSTEM

PHIVOLCS operates seismic monitoring stations all over the Philippines. These stations are equipped with seismometers that detect and record earthquakes. Data is sent to the PHIVOLCS Data Receiving Center (DRC) to determine earthquake parameters such as magnitude, depth of focus and epicenter. Together with reported felt intensities in the area (if any), earthquake information is released once these data are determined.

EARTHQUAKE PREPAREDNESS

SOURCE: PHIVOLCS

Tsunami

Albay’s exposure to tsunami has been recognized for decades. In 2006, residents participated in a large‑scale tsunami drill in Sto. Domingo, evacuating to designated high ground as part of a Pacific‑wide preparedness exercise triggered by mock warnings. While that event was a drill, it highlighted local awareness of tsunami threats and the need for effective early response.

WHAT IS A TSUNAMI?

A Tsunami is a series of sea waves commonly generated by under-the-sea earthquakes and whose heights could be greater than 5 meters. It is erroneously called tidal waves and sometimes mistakenly associated with storm surges. Tsunamis can occur when the earthquake is shallow-seated and strong enough to displace parts of the seabed and disturb the mass of water over it.

TSUNAMI THREAT IN THE PHILIPPINES

There are two types of tsunami generation: Local tsunami and Far Field or distant tsunami. The coastal areas in the Philippines especially those facing the Pacific Ocean, South China Sea, Sulu Sea and Celebes Sea can be affected by tsunamis that may be generated by local earthquakes. Local tsunamis are confined to coasts within a hundred kilometers of the source usually earthquakes and a landslide or a pyroclastics flow. It can reach the shoreline within 2 to 5 minutes. Far field or distant tsunamis can travel from 1 to 24 hours before reaching the coast of the nearby countries. These tsunamis mainly coming from the countries bordering Pacific Ocean like Chile, Alaska in USA and Japan. The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) and Northwest Pacific Tsunami Advisory Center (NWPTAC) are the responsible agencies that closely monitor Pacific-wide tsunami event and send tsunami warning to the countries around the Pacific Ocean.

The Philippines is frequently visited by tsunamis. On 17 August 1976, a magnitude 8.1 earthquake in Moro Gulf produced up to 9-meter-high tsunamis which devastated the southwest coast of Mindanao and left more than 3,000 people dead, with at least 1,000 people missing. Also, on 15 November 1994 Mindoro Earthquake also generated tsunamis that left 49 casualties.

TSUNAMI SAFETY AND PREPAREDNESS MEASURES

To enhance safety, the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), in partnership with PHIVOLCS and the Advanced Science and Technology Institute (ASTI), has installed Community Tsunami Detection and Warning Systems in key coastal areas of Albay. These systems combine tide sensors and “wet/dry” detectors that monitor sea level changes in real time and relay information to local authorities. When sensors detect conditions associated with a potential tsunami (such as rapid sea recession after a strong quake), LGUs can sound warning sirens and trigger evacuations.

Each one of us in the community should learn some important Tsunami Safety and Preparedness Measures such as the following:

- Do not stay in low-lying coastal areas after a felt earthquake. Move to higher grounds immediately.

- If unusual sea conditions like rapid lowering of sea level are observed, immediately move towards high grounds.

- Never go down the beach to watch for a tsunami. When you see the wave, you are too close to escape it.

- During the retreat of sea level, interesting sights are often revealed. Fishes may be stranded on dry land thereby attracting people to collect them. Also, sandbars and coral flats may be exposed. These scenes tempt people to flock to the shoreline thereby increasing the number of people at risk.

SOURCE: PHIVOLCS, DOST

Landslide

Albay Province is highly susceptible to rainfall-induced landslides and volcanic mudflows (lahars) due to its steep terrain, loose volcanic materials, and frequent heavy rainfall from tropical cyclones, shear lines, and the southwest monsoon. PAGASA regularly issues weather advisories warning that moderate to heavy to intense rainfall can saturate slopes and trigger landslides and debris flows, particularly in mountainous and upland areas of the province. During periods of prolonged or intense rainfall, PHIVOLCS releases lahar advisories for Mayon Volcano, cautioning that volcanic ash and pyroclastic deposits on its slopes may be remobilized into fast-moving lahars that can flow along river channels and threaten downstream communities. Hazard maps and preparedness guidelines from PHIVOLCS, together with rainfall warnings from PAGASA, are used by local government units to identify high-risk areas and implement pre-emptive evacuations to reduce loss of life and damage to property.

WHAT IS A LANDSLIDE?

A landslide is the mass movement of rock, soil, and debris down a slope due to gravity. It occurs when the driving force is greater than the resisting force. It is a natural process that occurs in steep slopes. The movement may range from very slow to rapid. It can affect areas both near and far from the source.

Landslide materials may include:

- Soil

- Debris

- Rock

- Garbage

LANDSLIDE TRIGGERS

- Natural triggers

- Intense rainfall

- Weathering of rocks

- Ground vibrations created during earthquakes

- Volcanic activity

- Man-made triggers

Movement can occur in many ways. It can be a fall, topple, slide, spread, or flow.

Flooding

Flooding is one of the most frequent natural hazards in Albay Province due to its exposure to tropical cyclones, monsoon rains, and shear line weather systems. The province regularly experiences heavy and prolonged rainfall that causes rivers to overflow and low-lying areas to become inundated, especially during the typhoon season.

Low-lying municipalities and cities such as Legazpi, Daraga, Guinobatan, Camalig, Libon, and Polangui are highly susceptible to flooding. These areas are located near major river systems and floodplains, where intense rainfall quickly leads to rising water levels and flash floods that can submerge homes, roads, and agricultural lands.

Flooding in Albay is often worsened by its proximity to Mayon Volcano. During heavy rains, loose volcanic ash, soil, and debris are washed down the slopes and river channels, resulting in lahar-related flooding. This type of flooding is especially dangerous because it carries thick mud and debris that can damage structures and farmlands.

The impacts of flooding include displacement of families, damage to infrastructure, loss of crops and livestock, and disruption of transportation and livelihoods.

SOURCE: PAGASA, PHIVOLCS

Storm Surge

A storm surge locally termed daluyong ng bagyo is the abnormal rise in sea level above normal tidal levels that occurs during a tropical cyclone. This rise is not caused by rainfall or tsunami activity but primarily by strong winds and low atmospheric pressure generated by the cyclone, which push ocean water toward and over coastal land. When a storm surge coincides with high tide, its height and inland reach can increase significantly, flooding areas that may otherwise remain dry. Big waves accompanying the surge further amplify coastal inundation and damage.

Why It Matters in Albay

Albay’s long, low-lying coastline along the Philippine Sea makes many of its coastal municipalities and barangays vulnerable to storm surge. Elevated water levels can inundate homes, roads, fishponds, and infrastructure, disrupt marine navigation and livelihoods, erode beaches, and pose life-threatening risks to residents. Communities near sea level — especially during the passage of tropical cyclones — are at highest risk.

How Storm Surge Is Assessed

PAGASA uses several factors when forecasting storm surge impacts:

- Cyclone strength and wind field — stronger winds push more water.

- Expected storm surge height — measured relative to normal high tide.

- Topography and elevation of coastal areas — lower elevations face greater inundation.

Storm surges are among the deadliest coastal hazards associated with tropical cyclones because they can arrive with little warning and overtop defenses or natural barriers. Being informed about what a surge is, how it behaves, and how warnings are structured significantly increases community resilience and safety.

SOURCE: PAGASA